for the public

for scientists

When a star rings, its magnetic field can increase the pitch of the sound or even muffle it altogether. By watching the star’s brightness change over time, we can “listen” to these starquakes for these effects and infer what the strength and shape of the magnetic field is.

We can do this even if the star is so far away that we can’t tell it apart from a point of light. We can also do this in some stars even if the magnetic field is buried underneath the star’s surface. This technique has already been used to measure the magnetic fields deep in the cores of many red giant stars, which Sun-like stars become when their cores run out of hydrogen.

Gravity waves are buoyancy-restored oscillations which propagate in stably stratified regions in stars. Magnetic fields can change the properties of gravity modes (standing gravity waves) by acting as an extra restoring force and damping mechanism. This allows seismology to measure the strengths and geometries of magnetic fields in pulsating stars such as red giants, intermediate-mass main-sequence stars, and white dwarfs (including internal ones).

These techniques have already been applied to measure (or bound from below) the magnetic fields of many red giants.

My “PhD offense” contains a public-oriented introduction.

gravity waves at strong magnetic fields

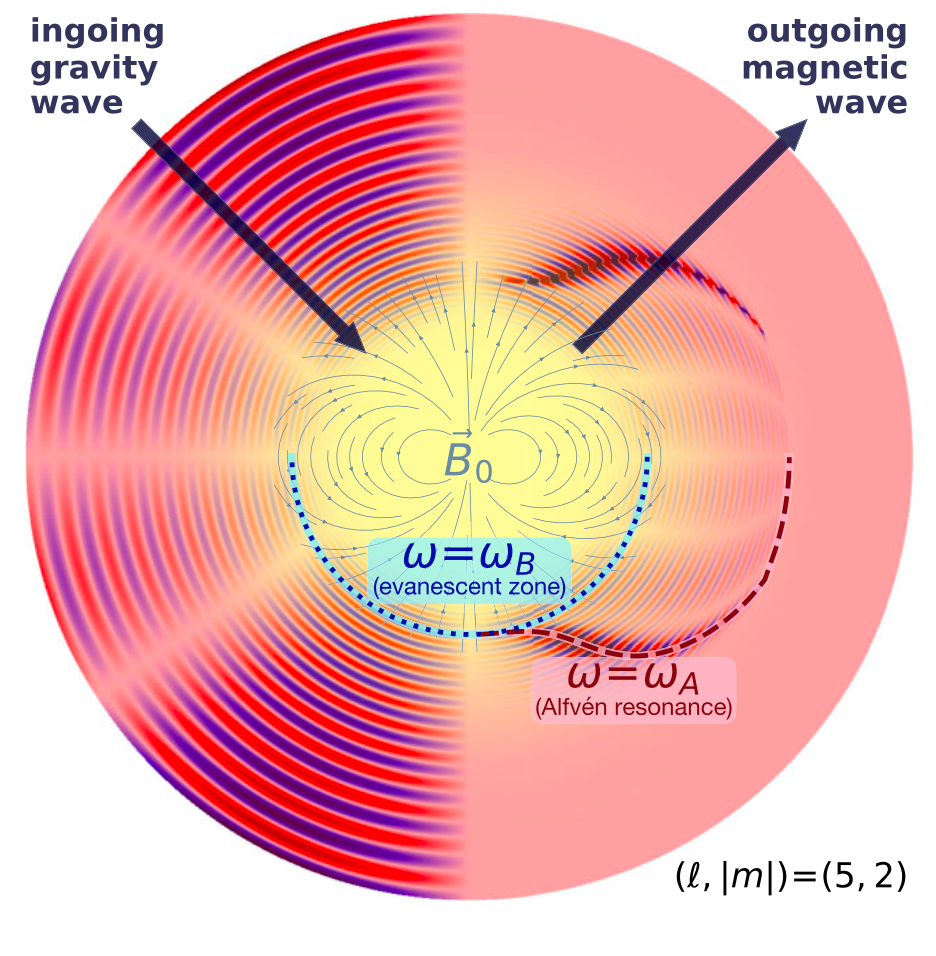

By making use of the flat, “pancake-like” structure of many stellar waves, I have predicted the effect of magnetic fields on stellar “ringing” without having to assume that the field is weak. It helps us explain in what ways magnetic fields can muffle stellar oscillations. It also allows astronomers to search for magnetic fields in the cores of stars which are stronger than those which we have ever found before using these methods.

I developed a formalism (the “traditional approximation of rotation and magnetism”) to predict the morphologies and frequencies of gravity modes under magnetic fields too strong for perturbation theory to apply. This approach relies on the fact that real gravity modes are often in the asymptotic regime (their wavevectors are approximately radial). It clarifies the nature of magnetic damping in the cores of red giant stars and provides us with accurate predictions for the frequencies of strong magnetogravity modes for future searches.

presented at:

- MIAPbP Workshop: Stellar Magnetic Fields from Protostars to Supernovae (Garching, Germany, November 2023), recording

- 7th TESS/14th Kepler Asteroseismic Science Consortium Workshop (Honolulu, Hawaii, July 2023), recording

published as:

- Rui, N. Z., Ong, J. M. J., & Mathis, S. (2024). Asteroseismic g-mode period spacings in strongly magnetic rotating stars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 527(3), 6346-6362.

- Rui, N. Z., & Fuller, J. (2023). Gravity waves in strong magnetic fields. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 523(1), 582-602.

finding oblique pulsators with phase information

Some stars have magnetic fields which are strong enough to orient starquakes along them. When this happens, different parts of the shaking surface of the star come in and out of view as the star rotates. Since many stars (including our Sun) ring in a random way, the regular pattern caused by the star’s steady rotation allows us to look for strong magnetic fields in stars without knowing exactly what they should sound like ahead of time.

Strong-enough magnetic fields can also misalign gravity modes from the rotation axis, causing the pulsation to be oblique. I showed that, when the pulsator is additionally stochastic (e.g., red giants), apparently distinct oscillation modes should display anomalous phase coherence which can be used to search for pulsational obliquity in a model-independent way. This signature is almost invisible to standard searches based on the power spectral density.

presented at:

- 9th TESS/16th Kepler Asteroseismic Science Consortium Workshop (Vienna, Austria, July 2025), recording pending

published as:

seismic magnetometry in white dwarfs

Once Sun-like stars burn or shed all of their hydrogen and helium, they shrink down into tiny, dead stars called white dwarfs. Since quakes on white dwarfs are very sensitive to magnetic fields, even small magnetic fields should be able to change their pitch or muffle them out.

We noticed that most quaking white dwarfs do not seem to display any of these magnetic effects. We use this to infer that the magnetic fields on most white dwarfs should be extremely low, in some cases less than a few tens or hundreds of times that of the Earth. These methods may help us learn how white dwarfs become magnetic.

White dwarfs also pulsate when they cross well-defined instability strips. The strong stratifications and low densities of their outer layers makes their gravity modes very sensitive to magnetism. This means that even weak magnetic fields should significantly modify the pulsation spectra of white dwarfs, or even damp out their oscillations entirely.

We use the non-observation of these effects to set very strong upper bounds on the magnetic fields of many white dwarfs (down to ~100 G in some cases) which often outperform other stellar magnetometry methods (e.g., spectroscopy).

published as:

- Blatman, D., Rui, N. Z., Ginzburg, S., & Fuller, J. (2025). Seismology and diffusion of ultramassive white dwarf magnetic fields. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.05343.

- Rui, N. Z., Fuller, J., & Hermes, J. J. (2025). Supersensitive Seismic Magnetometry of White Dwarfs. The Astrophysical Journal, 981(1), 72.