for the public

for scientists

Stars often form with close neighbors which they orbit for most or all of their lives. If these “binary” star systems are close enough, the two stars can merge together into a single star for many reasons. However, it is difficult to look at a star in the present and tell with certainty whether it has merged in the past. This is because we can only see the surface of the star.

By monitoring how a star’s brightness changes, we can measure the star’s “ringing.” Just like a hollow bell sounds different than a bell which is solid all the way through, measuring starquakes teaches us not only about the star’s surface but also its interior. Since we largely understand the interiors of isolated stars, we can tell if a star’s structure seems unusual. That is a strong hint that the star did not evolve by itself but has undergone a stellar merger in the distant past.

Stellar mergers are fairly frequent outcomes of binary stellar evolution. When they occur, they often leave behind remnants which are virtually indistinguishable from isolated stars based off of their surface properties alone.

Asteroseismology is a uniquely promising way to search for stellar merger remnants. Because the frequencies of stellar oscillation modes are sensitive to the bulk structure of the star, seismology can often identify stars with normal surface properties but atypical structures. Since the space of possible binary interactions is much larger than that of isolated stellar evolution, merger remnants are likely to have internal structures which are unusual in some way.

My “PhD offense” contains a public-oriented introduction. See also my Astronomy on Tap and Three Minute Thesis presentations.

asteroseismic fingerprints of stellar mergers

When stars reach the end of their lives, they inflate into red giant stars, engulfing any other stars that are orbiting them too closely. When this happens, the red giant star’s outer layers get heavier but the core of the star doesn’t change much. The red giant star otherwise looks very normal, and it is hard to tell that it swallowed a companion.

Since red giant stars with different masses are expected to have a different core structure, we can use starquakes to tell if the total mass of the star disagrees with the structure of its core. By listening to starquakes, we can often tell if a normal-looking red giant star has swallowed another star in the past.

Red giants often engulf close main-sequence companions. The result is a new red giant with a more massive envelope but a relatively intact core.

Although the star may look photometrically and spectroscopically typical, the asteroseismology can sometimes distinguish merger remnant red giants from isolated red giants. This is because the cores of red giants with ≲2 solar masses develop degenerate cores while those with ≳2 solar masses do not. The seismic mass, together with the g-mode period spacing, can identify stars of ≳2 solar masses but with degenerate cores. These can only form from stellar mergers.

This work has been featured on Astrobites and a Nature Astronomy Research Highlight.

presented at:

- 6th TESS/13th Kepler Asteroseismic Scientific Consortium Workshop (Leuven, Belgium, July 2022), recording, slides

published as:

the unusual red giant remnants of cataclysmic variable mergers

Helium-core white dwarfs are the stripped cores of red giant stars. We have never definitively discovered a helium-core white dwarf gaining mass from another star, even though we predict that they should exist. This may mean that, when a star pours mass onto a helium-core white dwarf, it quickly spirals in and merges before we can observe it. If this happens, the result is a red giant star whose core is much colder than usual (although still hot!).

These cold-core red giant stars have distinctive starquakes. In some of these red giants whose cores are cold enough, a lot of helium and other elements spill out of the core when it starts to burn helium. This causes the star to inflate more than usual. By looking for overinflated stars with unusual starquakes and elements at their surfaces, we may be able to discover these kinds of post-merger stars.

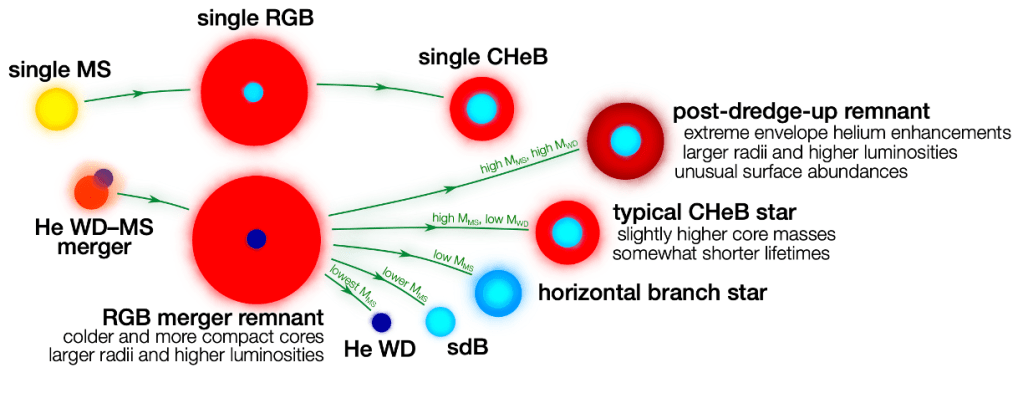

Despite predictions from binary population synthesis, no accreting helium-core white dwarfs have ever been found. This suggests that mergers between helium-core white dwarfs and main-sequence stars are fairly common. These mergers result in red giant stars with abnormally low-entropy cores and unusual seismic observables.

Merger remnants descending from massive-enough helium-core white dwarfs experience significant core dredge-up events during the helium flash, greatly enhancing the helium content of their envelopes. This causes them to overinflate due to the strong dependence of the hydrogen-burning luminosity on the mean molecular weight. It also dredges up a significant amount of other species such as carbon-12. This predicts that such stars should have a distinctive combination of seismic, photometric, and spectroscopic signatures.

presented at:

- COSPAR E1.19: Cataclysmic Variables and Related Systems as Probes of Accretion, Binary Evolution and Thermo-nuclear Explosions (Busan, South Korea, July 2024), slides

published as:

a giant planet escapes engulfment by its star

Baekdu is a red giant star which has exhausted the hydrogen in its core and swelled up to around eleven times the radius of the Sun. It also contains a Jupiter-like planet called Halla which orbits Baekdu about half as far away as the Earth does from the Sun.

Although Baekdu looks like a normal star, measurements of its starquakes reveal that it is actually undergoing helium fusion. This is something that stars usually only do when they expand to about the size of the orbit of the Earth. If this happened in the past, Halla should have been swallowed by Baekdu and destroyed. Halla’s existence is a puzzle.

We show that Halla could have survived if Baekdu ignited helium in a stellar merger with the stripped core of another red giant star. If this happened, Baekdu would have been able to reach its current stage without expanding much, saving Halla.

8 UMi is a red giant which hosts a Jovian planet 8 UMi b at a separation ~0.5 AU, visible to radial velocity observations. Measurements of the asteroseismic gravity-mode period spacing indicate that 8 UMi is actually core helium burning, a stage single stars typically reach only by expanding to ~0.8 AU (the tip of the red giant branch). This implies that 8 UMi b should have been engulfed. It is difficult to explain 8 UMi b’s present-day orbit with tidal or dynamical physics.

We show that 8 UMi could have been the remnant of a merger between a red giant and a helium-core white dwarf, which itself formed after a period of stable mass transfer. This allows 8 UMi to prematurely ignite helium before fully ascending the red giant branch and engulfing its planet.

This work got a lot of media attention, including from CNN, the New York Times, the BBC, Newsweek, Forbes, New Scientist, Science Daily, and Caltech Weekly. It was also featured on several YouTube channels, including Anton Petrov and VideoFromSpace.

published as: