I’m a doctor! Not the usual kind of doctor, but blood, sweat, and tears were certainly involved.

In 2020, I graduated from UC Berkeley with my bachelor’s degree and wrote a blog post summarizing my undergrad years. Finishing grad school has been a similar transitional event in my life, but also one which many fewer people experience. I think now is a good time for reflecting back on my experiences in grad school and hopefully demystifying the whole process a bit.

My PhD is in physics from Caltech, but I spent the vast majority of my time doing astrophysics in the astrophysics building (the Cahill Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics), especially on the half of the third floor allocated to the TAPIR group (a contrived acronym which presently stands for Theoretical AstroPhysics Including Relativity and Cosmology).

Looking back, my grad school experience was mostly ideal. It lasted five years, no longer or shorter than I wanted it to. While I had my own share of frustrating moments of being stuck, my growth as a researcher was monotonic and accumulated steadily over the years to the point where I now feel pretty autonomous and independent as a researcher. Although I was certainly exhausted by the end of this whole thing, I still haven’t had enough of academia. I’ll be starting next month in a prestigious prize postdoc position.

Unlike undergrad, my grad school experience highly deemphasized classes and placed personal recreation at the center of things. My experiences during these years therefore lack a lot of the simple structure that would usually be introduced by a rigid academic calendar. I think this typical of most people in my position. I consider this a fair warning for the following to read much more like a stream-of-conscious regurgitation of all of the things I can remember doing during these years, written during the point in time where the number of such things is maximized.

Before the storm

Graduate school started off pretty rough. What’s life without a unique challenge?

I started grad school the August right after the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. In March, I had been gearing up to go on a tour of the grad schools that I had gotten into. Once the pandemic broke out, the world ground to a halt. I was able to visit two of the four grad schools that I was heavily considering—these happened to be astrophysics programs, which tend to have their prospective visits earlier than physics programs. Caltech was one of the schools I didn’t visit.

Working off of incomplete information was really stressful: for every pair of schools, there was some period of time during my decision period where I thought I was definitely going to one or the other. Though mine was a “good problem to have,” I had a tough time locking in a decision which was likely to affect the rest of my academic and social life. Even if things would probably turn out fine in the end, they would turn out fine differently. I did as much homework as I could to minimize the amount of regret—it’s fine if things go belly up, as long as it wasn’t my fault for not being comprehensive enough. Nevertheless, I think some doubt about which school I should have gone to lingered for about a year into grad school.

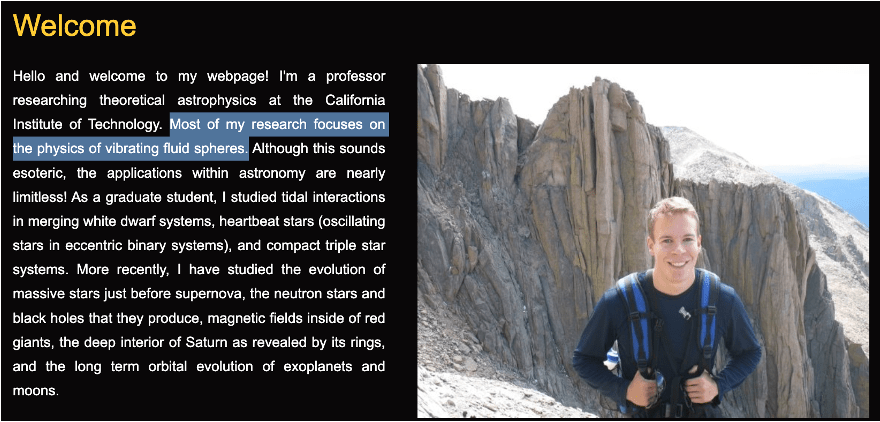

I ultimately chose to come to Caltech, knowing that I wanted to work with Jim Fuller, an early-career not-yet-tenured professor working on stars. Jim’s group was small and had only two grad students, one of whom was a classmate of mine at Berkeley. At the time, Jim’s website looked like this:

The highlighted line caught my eye: “Most of my research focuses on the physics of vibrating fluid spheres.”

In my mind, there are two broad ways of doing theoretical physics. One can be comprehensive, taking into account every piece of physics and putting it all into a big model. One can also be reductionist, taking out as much physics as possible until one is left with only enough physics to reproduce the phenomenon of study. Both methodologies are highly valuable, and every theoretical physicist has to do a bit of both, although usually they lean in one direction or another.

I would certainly say I’m a reductionist by disposition. I’m a pretty distracted person who is not all that detail oriented, and I find it hard and generally unpleasant to do a thorough accounting for more pieces of physics than I can reasonably simultaneously hold in mental RAM. In contrast, I’ve found that my strengths lie in distilling complex mathematical behaviors of physical systems into a few sentences of simple physical intuition. Anyway, I’ve always found that I care much more about the why? than the how much? side of physics.

“Vibrating fluid spheres” suggests a toy-model forward approach to doing physics. I can understand what a vibrating fluid sphere is. I would much rather study a vibrating fluid sphere than a star. Who cares about those, anyway?

Year One (2020–21): Breaking Ground

Life as an inmate

The pandemic lasted for longer than the weeks that people thought it would. Problems lasting for much longer than expected is a universal theme of grad school.

In the words of a tongue-in-cheek but oddly accurate Google Review, I started grad school in a “Swedish prison.” In August, all in-person Caltech grad students were quarantined for a week in the Bechtel Residence, an undergrad dorm with concrete walls which might as well have been lined with lead. I felt safe from the apocalypse. This was unfortunately not a hypothetical.

In addition to being hit hard by the pandemic, the Los Angeles area was also afflicted by the Bobcat Fire. The blaze was visible from the top of nearby parking structures. It made the air outside very smoky and difficult to breathe. As if we all needed another reason to wear a face mask. The nation at the time was also racked with countrywide protests following the shooting deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

Despite our mostly virtual interactions, our grad student class was very social. A few months before grad school, a majority of the ~200 new grad students coalesced around a Discord server which had regular social calls leading up to our start. Getting to know people was essential.

I spent most of my week in the nuclear bunker reading and working through resources on stellar oscillations, memorably Bill Chaplin & Andrea Miglio’s review on solar-like oscillations and Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard’s Lecture Notes on Stellar Oscillations. Originally, this was all in the service of a project idea related to the effects of a certain kind of magnetic dynamo (the Tayler–Spruit mechanism) on the damping observed in many red giants. After a week, I left quarantine with my fellow detainees and moved into my grad apartment in the Catalina Apartments (“the Cats”), my home for the next year.

In Winter, fellow grads Sarah Habib and Hannah Manetsch moved into another Cats apartment over which they had sovereignty for the next five years. As the de facto meeting place for social activities for the remainder of grad school, the apartment was quickly designated the “Vibe Shack.” Owing to the small size of my research group and isolation from the astronomy department, the majority of my friend group would turn out to come from the SXS (numerical relativity) and LIGO (gravitational wave astronomy) groups.

Starstruck

A few weeks later (now long out of quarantine), Jim realized the original project idea wasn’t likely to work, long before I got around to fully understanding it in the first place. Instead, he asked me to work on an essentially fully-formed idea to use asteroseismology to find stellar merger remnants. Looking back, it was a perfect “training-wheel” project for learning the physics and methods involved in this line of research in the service of a pretty simple idea (which also turned out to be fairly high impact!).

Despite coming to Caltech for the express purpose of studying stars, I knew very little about stars. Like many similar programs across the country, UC Berkeley’s astrophysics major program was very open-ended. I once worked out that you technically only needed to take a single class in the Astronomy Department to receive an astrophysics degree. One of the more rigid requirements was to take any two of the following three classes: planets, stars, and cosmology:

Guess which one I didn’t take?

After the main body of the project was complete, I spent a huge amount of time trying largely unsuccessfully to generate models of stellar merger remnants using an alternative, “entropy-sorting” scheme. I think I wanted to preliminarily check my results against another prescription in the literature. I had not yet developed enough confidence in my field to fully understand all of the uncertainties in my field. In hindsight, this effort wasn’t “worth it.” But I think these long periods of deliverable-less struggle were ultimately valuable for teaching me some of the pragmatics of research: how to have new ideas, assess their promise, and cope when they fail. I am a stronger researcher because of all of the bad ideas I have had.

What it feels like to run out of school

Early in grad school, most grad students are still taking courses to fulfill some of the more structured requirements of their degree. I was no exception.

As did most grad students, I was much less tolerant to large course loads than I was in undergrad. When I graduated high school, there was some part of me that was permanently unwilling to tolerate the same level of menial work—fully stacked days with homework assigned every afternoon due to the next morning. Permanent senioritis. Grad school was no different, and probably worse. Whereas I was usually taking four rigorous technical courses at a time as an undergrad, as a grad student I never took more than two, and prioritized them much less.

But this attitude was for the best. At the heart of it, grad school isn’t really about classes at all—it’s about research. I like to describe grad school as like learning to become a blacksmith. I imagine the process involves something like being recruited as the apprentice to the best hammer-maker in the entire world, probably the person who even invented the concept of a hammer or some adjacent person. Over several years, you learn how to make hammers from this person (the “advisor”), gradually perfecting your craft and even making a few tweaks to make new, better hammers that the world has never seen before. All throughout, there are people who buy your hammers: as shaky as your handiwork was, your hammers are of decent and increasing quality, and you’re actually getting paid to learn how to make hammers. Finally, at some point, your blacksmith “advisor” grants you the rank of master blacksmith, certifying you as someone who can make hammers by yourself.

Classes are not a big part of that. Wisely, I spent most of my time making hammers instead.

I had somewhat arbitrarily applied to Caltech’s physics PhD program rather than its astrophysics program. This turned out to be very lucky. Unusually, Caltech’s physics program had many fewer requirements than the astrophysics program. Whereas the astrophysics program prescribes a rigid curriculum of astronomy courses, the physics program required only six technical courses with almost infinite flexibility about which to take, and allowing all of them to be taken pass–fail. The astrophysics program also required attendance at a weekly journal club and assigned all of its students various department-maintaining “chores.” I think the physics program is also easier to get into. While I lacked the trauma-bond characteristic of the astrophysics grad students, I was very grateful for my choice.

I used this freedom to spend some time expanding my horizons in my last months before specializing hard into theoretical astrophysics. In addition to taking an introductory stars class, I also took a class on solid-state physics. I figured that no physicist should go without at least a basic background in the most heavily populated field of physics. I had lots of fun these days. I spent the rest of the year taking fluid dynamics, complex analysis, high-energy astrophysics, and order-of-magnitude physics.

These classes gave me lots of tools. I had fun.

Cleaning up odds and ends

At top schools like Caltech, every incoming student has some significant undergraduate research experience. I noticed that, with almost no exceptions, every student had some unfinished undergrad project that they were finishing up early in grad school.

In 2019, I was an REU student at Northwestern University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA), where I worked on globular cluster dynamics with Fred Rasio and Kyle Kremer. At the time, Kyle was a highly productive, final-year grad student. He has since become a professor at UC San Diego: time flies…

My project involved matching up globular cluster models to observations of real globular clusters. Based on which clusters happened to resemble our models, we chose seven globular clusters to study in detail. Coincidentally, at around the time that we were finishing up this paper, a highly publicized study dynamically detected a population of dark objects in one of these clusters, NGC 6397, and conjectured that they were black holes. Knowing this wasn’t the case, we also wrote up a short Research Note showing that the objects they detected matched up perfectly with the white dwarfs these clusters have. Kyle took the time to write a paper discussing white dwarfs in globular clusters in general. While I had done research before, this all felt like research placed within its proper context: a global real-time dialogue between scientists trying to figure out what’s going on with the universe.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded in part to Andrea Ghez for the discovery of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Since she was the PhD advisor of my undergrad advisor Jessica Lu, I was excited that my first-ever first-author paper had a Nobel laureate on it. This was an early glimpse into how small the academic community is. In a single academic career, I could see how it would be possible to eventually “know everyone.”

A healing world

In some sense, grad school is an escape from many responsibilities and gritty truths in the “real” world. On the other hand, it is hard to be insulated from the world around us.

COVID-19 was of course the obvious example of this. It shaped our day-to-day lived experiences. Even for theorists for whom research is a plausible shower activity, the phrase “I hope you’re doing well in these trying times” was a well exercised component of our lexicons. The first COVID-19 vaccines were developed in the later months of 2020, and I got vaccinated in March 2021 in the sterile environment of a college parking lot by folks in camouflage.

November 2020 was also the presidential election pitting incumbent Donald Trump against Joe Biden. My political consciousness started in 2014 while I was in high school—I imagine it would be hard for even slightly older folks to understand that Trump has been a permanent fixture of politics since I knew anything about it. I was ready to stop having to worry so much about nonsense at the highest arenas of our civil discourse.

I decided ahead of time to have my first beer on Election Day, November 3rd, 2020. I figured that I would either need a drink to celebrate the outcome or a drink to forget it. As it turned out, the election was much closer than was comfortable, and the outcome wasn’t really settled for another few days as straggler states took their time counting their ballots. Uncertainty in our new government lingered until the special senate elections of Georgia Democrats John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock to the Senate, barely forming a Democratic majority in the House.

Later in the year, my fellow grad students and I watched thousands of Trump supporters storm the Capitol building on January 6th, 2021, two weeks before Joe Biden’s inauguration. Trump was apparently ostracized by all major media institutions, presumably trying to follow the winds of change. Isn’t it funny that we thought we would be rid of him?

Year Two (2021–22): Sowing Seeds

Wedded to the whiteboard

Due to a perpetual shortage of office space in TAPIR, students were only assigned office space in Cahill from their second year onward. I opted for a quiet, windowless office on the interior of the floor, on the theory that I would be more productive if I didn’t know that it was getting late outside. This sort of worked, but was probably not great for my mental health. For the first two years of grad school, I was close to nocturnal. A friend Isaac Legred and I moved into a new apartment roughly 30 minutes away from Cahill by walking.

At the beginning of the school year, I wrapped up my previous project. It was well-received enough to get attention from Astrobites and Nature Astronomy and, as a result, I was asked to referee a paper for the first time. There’s nothing better for imposter syndrome than being thrown into the deep end, I suppose.

I then went to work on a very different project aiming to understand the magnetic suppression of mode energy in red giants. While the previous project was mostly computational with some basic physical arguments thrown in, this project was much more analytic in nature. After a while, it became clear that my goal was to essentially understand the properties of a certain differential operator using a combination of pencil-to-paper math and a simple numerical solvers. I was about to get well-acquainted with the theory of differential eigenvalue problems with internal singularities. I was overwhelmed.

It was unfamiliar territory for Jim as well. We had a lot of meetings full of long mathematical discussions whose ultimate conclusion was usually uncertainty. I oscillated with high frequency between being sure that I had derived the Higgs mechanism to feeling like an honorable ship captain going down with his sinking ship which had left harbor with an array of decorative holes.

I thought about this problem all the time, although it took a very long time before I gained enough confidence in my lack of important mathematical mistakes. I was constantly afraid that I had at some point committed some egregious math typo that would invalidate all of my work. I think this sort of insecurity is very common for early-career researchers, but I think it reaches a whole new nature for pencil-to-paper projects. There is no new data, novel observations, or groundbreaking simulations in theory projects like this. If I got it wrong, I would get it wrong hard.

Stockholm Syndrome

Having already taken six classes, I think I was probably already done with all of my course requirements by the end of the previous year. Nevertheless, I had been taking courses essentially continuously since first grade in 2003. I guess you could say I was institutionalized. I spent the first two terms taking the first two courses in general relativity, as well as quantum field theory and high-energy astrophysics. These were highly enriching experiences. Nevertheless, by the end of this, I was ready to be done with classes forever. I still loved to learn, but I think my mentality had transitioned to preferring to learn outside of a structured, regimented environment. From here on out, I was mostly trying to learn things that nobody on Earth knew. It would take me longer to get fully used to that.

Learning in a structured environment didn’t totally end, however. Around this time, fellow grad student Nadine Soliman (soon to start as a Hubble Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study) invited me to a reading group on fast radio bursts (FRBs) with her, Professor Sterl Phinney, and a few postdocs Dongzi Li and Liam Connor (now faculty at Tsinghua University and Harvard University, respectively). Though the irony was not lost on us that neither of the grad students were actively working on FRBs, it was still an immensely educational experience which broadened the number of talks I could understand.

ARC Seminars

Despite formally being a grad student, I still felt like I was doing virtual school. Grad school wasn’t living up to the sauna of intellectual discussion that I had hoped. I didn’t even meet my advisor in person until halfway through the first year, and only then in order to borrow a book on stellar oscillations. Although things started to open up gradually during the first two years, campus regulations would sometimes tighten again after isolated COVID outbreaks. We all got used to spitting in a cup and syringing it into a vial for our weekly COVID tests. It still felt like doing a PhD in paintbrush studies on neopets.com.

At the end of 2021, I decided to start an informal talk series to make an excuse to talk about science outside of my immediate scope. I honestly felt very self-conscious about this: was I trying too hard? Would this actually be a “real thing?” Though I think I knew this intellectually at the time, I came to realize more deeply that the only thing that makes something “real” is if it happens, if we put effort into it, and if we get some value out of it. Running the ARC Seminar in TAPIR turned out to be a highly educational experience in academic logistics, and also taught me a lot of science that I would never have been exposed to otherwise. I also found it immensely interesting to hear my friends explain the key ideas of their research fields in detail.

Seeing the world

Sometime in 2021, folks in my CIERA circle started to circulate the announcement of a conference at Aspen on the dynamical formation of gravitational waves. I had never been to a conference before and, moreover, wanted to see my friends at CIERA again. I struggled to find funding for it until I said the right words to administration who realized that I had a discretionary fund associated with my first-year fellowship at Caltech. Although I originally didn’t apply for a talk, I decided to give one last minute. This turned out to be a very valuable experience.

I landed in Aspen the night of the first conference day, owing to a cancelled flight. Given Aspen’s small airport and temperamental weather, I have since been taken to understand this to be a common experience. Owing to the pandemic, talk slots were unusually easy to come by, and almost every conference participant gave a talk. I feel in hindsight that it was incredibly valuable for me to have had this first talk experience as early as I did.

My flight out of Aspen was also cancelled, and, amidst the new gamma variant, a large number of conference participants were testing positive for COVID. I escaped on a last-minute flight from Aspen. Since the new flight was delayed, I narrowly missed my connection at Denver Airport and stayed the night at the airport. I spent the early part of the night playing cards with Floor Broekgaarden, then a Harvard grad student who is currently a professor at UC San Diego (alongside Kyle Kremer). As a San Diego native myself, I guess this is where all the cool kids hang out.

At the end of the year, I traveled to Leuven, Belgium for the TASC6/KASC13 Workshop, the latest installation of the largest asteroseismology conference. Due to a combination of the new delta variant and an airport strike, I had a flight cancelled three consecutive times, staying in London on an extended layover at the home of fellow grad student Cat Felce. I booked another last-minute flight to Brussels and eventually made it to the conference a few talks into the beginning of the first day. As it would turn out, this was only the beginning of my extraordinarily bad luck regarding flights during grad school.

I met a lot of great folks at the conference, including a long-time collaborator and mentor Joel Ong, then a grad student at Yale and now a Hubble Fellow at the University of Hawaii. I also gave a fairly well-received talk on the last day of the conference. I felt wider appreciation for my new research for the first time.

Overall, I found “my people.” Stellar physics is not a very popular discipline in the United States, and is much more popular in Europe and Australia. Asteroseismology was even more niche than that. As it would turn out, the good thing about this was that I got to travel all over the world. The bad thing about this was that I had to travel around the world. The novelty had not worn off yet.

Year Three (2022–23): Small Adventures

Adventures as a stellar engineer

Sometime in 2022, I tied up my semianalytic project on strong magnetogravity waves. While it was over, I felt that I had written a pretty impenetrable mathematical paper still full of uncertain physics and whose overall impact was unclear even to me. Given that this paper is now at the foundation of a lot of my current research, it would take me yet more time to fully realize why what I had done was important. From here on out, I would try very hard to understand the broader impacts of my work before publication, and not after.

Progress on this front would finally come toward the end of the school year, when I started a collaboration with Joel and Stéphane Mathis, the latter a researcher at the CEA in France and one of Jim’s collaborators. I converted my fairly esoteric work on magneto-asteroseismology to a method for generating concrete, observational predictions. At this year’s installation of the TASC Workshop in Honolulu, I was able to show off some of this work. Coming to a regular conference for the second time is when you really start to feel like you’re seeing old friends again. It helped that I understood many more of the talks, too.

My next major task would be to try to perform one-dimensional simulations of failed common-envelope events. The basic idea was that, when a star swallows another star, it is possible for the swallowed star to kick out a lot of mass before being destroyed. While this is a super messy process, we had some idea that we could use the one-dimensional stellar evolution code MESA to produce some estimates and examine some phenomenology.

MESA is a major cornerstone of the field of stellar evolution. It was released in 2010 by an eccentric retired computer scientist Bill Paxton, who recently passed this last July. Bill got his PhD in the 1970s and, as one of the co-founders of Adobe (yes, that Adobe), contributed substantially to the field of computer science, notably as one of the key designers of Postscript (a predecessor to PDF documents). Retiring early and looking for something to do, Bill sat in on some classes at UC Santa Barbara and met Lars Bildsten, a key figure in stellar evolution. After Lars made Bill aware of the proprietary nature of stellar evolution codes, an outraged Bill spent six years writing an explicitly open-source stellar evolution code. At present, it is by far the most popular stellar evolution code, and has democratized stellar evolution as a subject of study.

As it turns out, my task of simulating a stellar merger in MESA was much harder than I expected. Much of my third year was spent trying to deal with any number of bugs which would cause the code to crash. MESA‘s development also suffers from the unusual feature that more recent versions of the code are more likely to crash (owing to things like stricter error tolerances), and it is common practice to downgrade MESA strategically in order to get a present simulation of interest to run. Stubbornly, I resisted doing this for much longer than I should have. The fact that the problem was intrinsically three-dimensional anyway was additionally demotivating.

I advanced to PhD candidacy following my candidacy exam at the end of my third year. Though stressful, oral exams really have a way of burning information into your mind. If you fail to answer a question in that sort of confrontational context, you will never forget the solution. Sterl, one of my committee members, mentioned that he once had a student working on one-dimensional simulations of stellar mergers and suggested I work on my other proposed project, which was probably more promising.

It was just as well—my application to work on these stellar merger simulations at the Center for Computational Astrophysics was denied. I had applied there because I wanted a change of scenery in a time of some personal struggles. The new project was destined to be one small part in the change that I wanted. That’s roughly how I came to work on the products of mergers between stars and white dwarfs, which consisted of a summer of trying futilely to accrete hydrogen onto a helium white dwarf in MESA. In our field, the apparently simple but actually highly nontrivial task of creating a desired stellar model has earned the entertaining name “stellar engineering.”

In parallel with all of this, I was kept busy by my role in a new collaboration. The previous school year, Jim included me on a collaboration aiming to characterize and explain the existence of an unusual planetary system. The collaboration was led by Marc Hon, then a Hubble Fellow at the University of Hawaii (with Joel) and now an incoming faculty at the National University of Singapore. While I struggled initially with great frustration to get the required MESA models to run, I eventually finished ahead of schedule. My nascent skills as a MESA user were converted into authorship on a Nature paper which, owing to Marc’s efforts, received an extraordinarily large amount of press (on release day, second only to the NANOGrav announcement of the detection of a stochastic gravitational wave background).

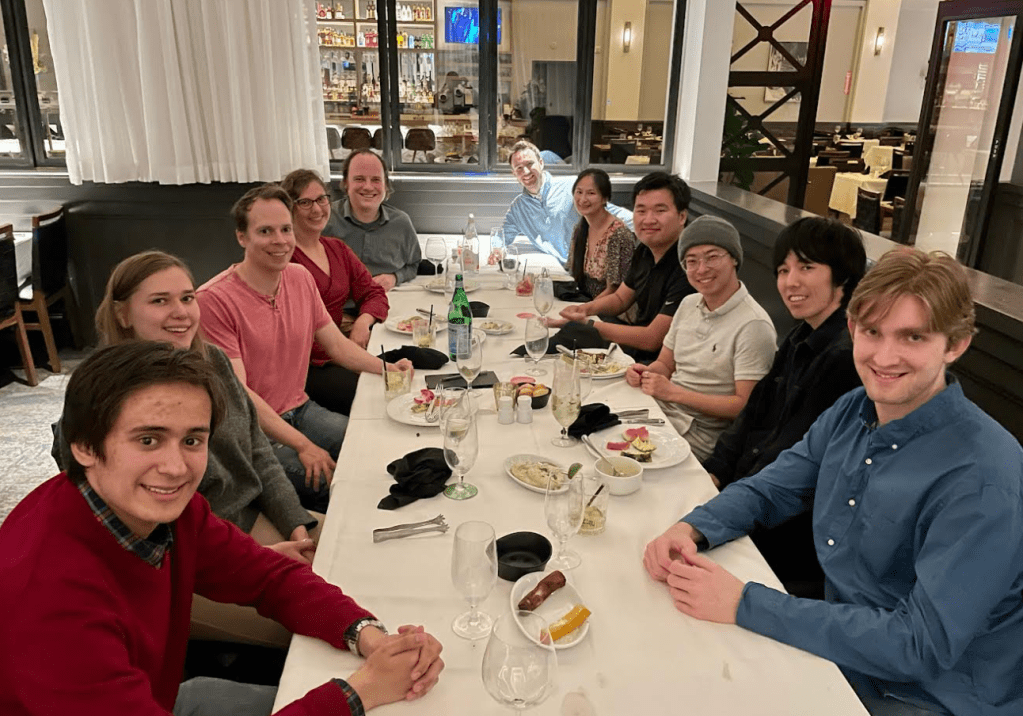

At the beginning of the school year, Caltech hired a prize fellow Daichi Tsuna to work on supernova-related science. In our group, Daichi was a friendly presence who was one of the only folks who would regularly show up to my largely pitiful attempts to start a group lunch. In April, Jim got tenure. The celebratory dinner was totally organized by then-student Linhao Ma, now a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. While it didn’t come as a surprise to anyone, it was nice to know that my advisor wasn’t going to get fired before I graduated.

Look at me, I am the teacher now

Between my first-year fellowship and the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, I had four years of funding, without any teaching obligation. However, teaching was something that I really wanted to do. While I had some tutoring experience earlier in grad school with Caltech Y (virtually in the first year and at John Muir High School in the second), I specifically wanted to learn how to teach in a classroom setting. After some push and pull, Jim and I came to an arrangement where I would spend the third year being funded by a teaching assistantship. With this year included, that was my full five years of funding taken care of.

Undergrads at Berkeley seemed to have a “depression culture” which revolved around people performatively complaining about the difficulty of their classes and coping that their low grades would be compensated to employers by the high status of their school. I definitely had some periods of struggle at Berkeley, but at least my own experience was that most of my requirements were fairly reasonable.

Caltech is different. While its grad students seem to have fairly typical grad student experiences, Caltech undergrads seem like tortured souls. They are subjected to a battery of intense academic requirements, all within the culture of taking several-too-many technicals. Unusually, Caltech students mostly seem to think about research as a summer activity, since they are so busy the rest of the year. I now found myself in the position of teaching them.

For the fall and winter, I taught introductory oscillations (with Sergi Hildebrandt) and electromagnetism (with Gil Refael). Being a TA for these courses challenged me to develop interesting resources for these classes while dealing with the pragmatics of teaching and trying to temper my overly idealistic expectations about what information I could get across. I spent my full weekends developing custom problems and notes for the topics, in hindsight often way overdoing it. In the spring term, I was one of Sterl’s TAs for order-of-magnitude physics. One of my most valuable lessons was learning to view struggle as a resource: there is a finite amount of struggle that a student is willing to tolerate before tuning out, so it should be budgeted to teach the student as much as possible. Despite feeling like I didn’t do all that great a job, I won that year’s R. Bruce Stewart Prize for Excellence in Teaching Physics. Given how many mistakes I felt like I had made over the year, to this day I’m not quite sure if that was something I deserved.

Another pedagogical goal of mine for the year was to learn how to mentor. Jim forwarded me a subset of roughly a dozen emails from undergrads soliciting research, mentioning that the cadence of such emails during the “off season” was about one per day. Once my name was attached to a posting on Caltech’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship website, I received maybe a dozen per day for a few days. It put into even starker perspective what my allocation of time would have to look like if I continued on in academia.

After a thorough selection period, we ended up selecting Stephon Qian for my project. Stephon was, at the time, a Cornell undergrad who had done impressive work on dynamics with Dong Lai, Jim’s PhD advisor. Stephon proved to be a talented student, and working with him on the rotational evolution of post-engulfment red giants proved to be a very enriching and rewarding experience. Stephon is currently a grad student in astrophysics at UC Berkeley. Our group also recruited a strong Caltech undergrad Emily Hu for a different project—this fall, Emily starts her own PhD at the University of Toronto (in these turbulent times, wisely getting out of the country).

Touching grass (and snow and sand)

It took me much longer than it should have for me to appreciate the importance of doing non-academic things. As an undergrad, I essentially gave physics 100%. When I wasn’t doing coursework, I was doing research, and when I wasn’t doing research, I was teaching or doing outreach or doing club work (the club being, of course, physics-related). While things turned out very well for me academically, the stress associated with and adjacent to grad school required some kind of counterbalance. I was in grad school to have fun and learn things—it became clear to me that I should prioritize having fun and learning in general, whether or not they had to do with physics. This year, we took advantage of our locale and traveled up to Mammoth for a few days of skiing.

In Fall 2022, Nadine Soliman told me about a dance show exhibiting the various kinds of dance clubs and classes at Caltech. Caltech’s small (roughly two-thousand strong) student population means that its clubs are mixes of undergrads, grads, postdocs/staff, faculty, and unaffiliated members of the community. After taking classes in tango and West Coast Swing, I made the latter my hobby for the rest of grad school. On days where I got stuck in research or was otherwise not feeling great, evening West Coast Swing classes were a welcome thing to turn to. Not too long after, in Winter 2022, I joined the Caltech karate club, a mostly community-member-run class which revived my interest in a childhood hobby which was put on hold when I went to college.

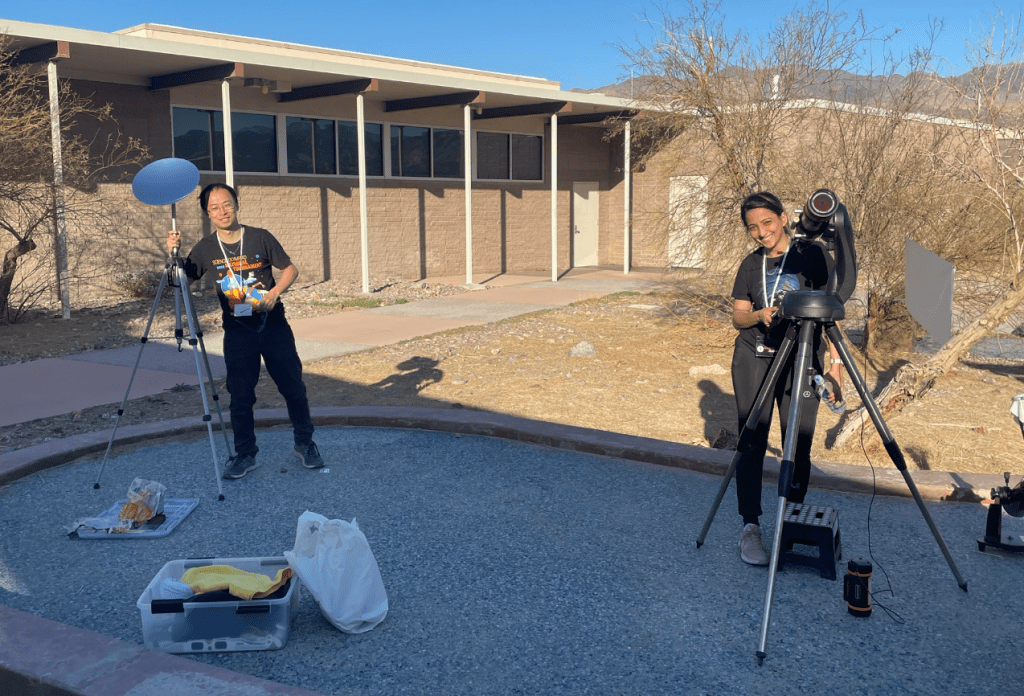

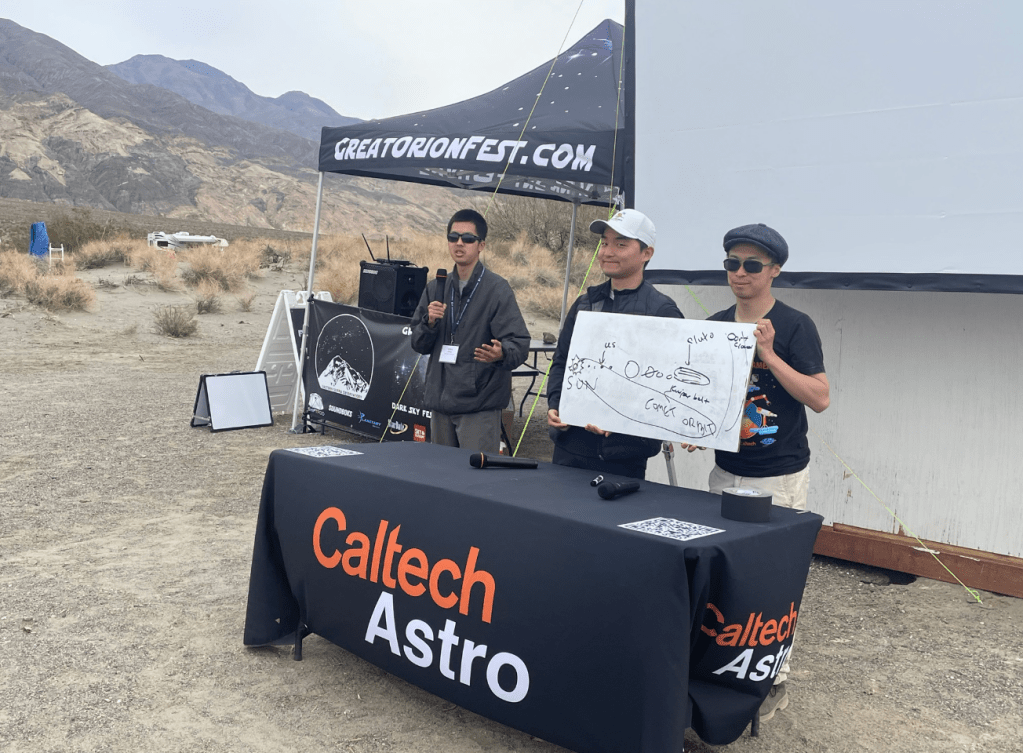

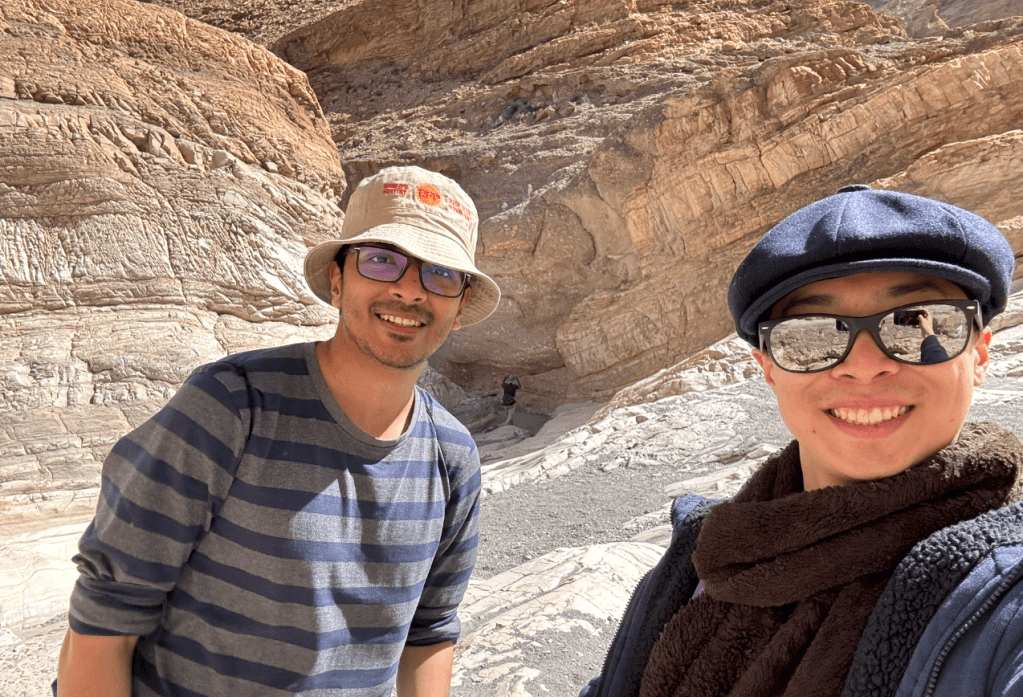

This was also the year that I really started to get into public outreach with Caltech Astro Outreach, which is led by a jovial research scientist Cameron Hummels who, outside of organizing and emceeing the vast majority of the outreach events in the department and doing his own research in galaxy formation and evolution, also holds the world record for the fastest unassisted off-trail crossing through Death Valley. Characteristically, this year, I came along on outreach-related trips to Death Valley and Panamint Valley for dark sky festivals.

This year, I endured a wisdom tooth extraction. This school year also saw the first public release of ChatGPT, which was destined to change the world (not always in positive ways…).

Year Four (2023–24): Swimming in the Deep End

Getting my bearings

While I grew a lot as a researcher throughout grad school, I think my fourth and fifth years were probably around the time that I really felt autonomous and independent. Identifying and executing research projects requires identifying interesting open problems, which means understanding the state of the field well enough to know (1) that the solution to the problem is likely not known, or at least not known widely, and (2) that other people are likely to find it interesting. It also means enough confidence in one’s own knowledge to be pretty sure about these things. This year was probably the first year where I really felt able to do this.

This was the year that I completed my projects on stellar mergers (with Jim) and magnetism (with Joel and Stéphane). The former taught me a lot about the physics of stellar interiors, and the latter forced me to learn a lot of the details of the theory of asteroseismology. These two threads, common across my PhD, remain at the center of my research today.

Notably, these projects also made me more conscious of financial realities within academia. Very roughly speaking, astronomy as a field has three main journals of roughly equal prestige: the Astrophysical Journal (ApJ), Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A), and the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). While the other journals charged a fee to authors (~$3000), MNRAS made its money through reader subscriptions, and it was free to publish in it. This changed for papers which were submitted past the end of 2024 when MNRAS transitioned to an “Open Access” model. As a result, my paper with Jim was instead submitted to the Open Journal of Astrophysics, an excellent rising alternative journal which avoids author fees by being a “cover journal” on top of the arXiv preprint server. My paper with Joel and Stéphane went to MNRAS, but only because we were able to submit it right before the end of the year when the new policy went into full effect.

Starting in the fall, with the Caltech Connection program, I mentored a PCC student Connie Li as she looked into possible asteroseismic signatures in main-sequence stars. Not too long after, Connie transferred to UC Berkeley (the best school in the world) to start a promising career in aerospace engineering.

In contrast to previous years, much of my travel in this year revolved around broadening my interests and meeting new communities. In October, following a private retreat of astrophysicists to an isolated ranch, Lars Bildsten invited me to a valuable week of visiting the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics.

The following month, I had a pretty productive two weeks at a MIAPbP Workshop on stellar magnetic fields, which at the time was only somewhat adjacent to my work. There, I became involved in an “off-topic” collaboration trying to explain a particular species of unusual white dwarf that ended up being an incredibly educational experience (aside from thinking about some pretty cool science!).

The following summer, I returned to Garching to visit the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics for a private get-together, meeting many new folks in my field. I also opted for the cataclysmic variable session of the large COSPAR conference in Busan, South Korea (an unfamiliar crowd), rather than joining my old friends in Porto, Portugal for the latest TASC Workshop (during which time the Trump assassination attempt occurred).

For much of the school year, renowned theoretical astrophysicist Re’em Sari (at Hebrew University, formerly at Caltech) stayed at Caltech for his sabbatical. Caltech also newly hired Elias Most, an extremely prolific computational relativist and fluid dynamicist, who would become a friend and informal mentor and would later join my PhD committee.

At the end of this year, Jim’s first two grad students, Linhao Ma and Sam Wu, finished their PhDs and went off to prestigious prize postdocs at Princeton and Carnegie Observatories, respectively. Given the youth and small size of our group, the two had lit the way for my PhD by enduring the group’s growing pains, and group meetings were quieter when they left. After Linhao left, I took over his desk in his spacious windowed office. I was destined to share it with three numerical relativists, from whom I learned by osmosis much more about general relativity than anyone ever should need to.

It was the end game, now.

Adventures in and out of the big blue house

At the beginning of summer, following an exceptionally bad landlord situation, I moved from my old apartment to a six-person house only a few blocks off of campus. The house was built in 1906 and totally painted blue, and, not too long ago, was the setting and centerpiece of an incredibly strange surrealist movie which someone has uploaded to YouTube in its entirety. Prior to having moved in, the house had been occupied by a group of extremely rowdy and notoriously problematic undergrads. To set the tone, when we visited for the first time, the undergrad living in the room that would later become mine had removed all the normal lightbulbs and installed deep red ones in their place. Both in spite of and because of our adventures in this house, this house made for an overall peaceful place to finish up my PhD, all things considered.

Outside the house, this year also had its fair share of leisure travel. In the fall, I traveled with my mom to her hometown in Yanshan County, Hebei, China, for my grandmother’s birthday. It was the first time I had been back to China in about a decade.

After seeing the partial version of the October annular eclipse, my mom, sister, and I traveled to Austin, TX in April to see the total solar eclipse, driving up to Waco to avoid some bad weather and maximize totality.

I spent a lot of this year getting acquainted with new styles of dance and generally meeting a lot of cool people in dance spaces. I counted down the seconds to the beginning of the 2024 New Year at the revival of the Angel City Fusion social dance, an event for the highly versatile fusion style of dance. The next month, my childhood friend Justin Mailom and I spent a weekend at the Fiddling Frog dance event, focused around Contra dancing (a type of folk dance). Later in the year, I went with Caltech’s West Coast Swing club first to the High Desert Dance Classic in Lancaster, CA followed by Jack n’ Jill O’Rama in Garden Grove, CA. These events (and many others) healthily introduced me to a lot of social contexts outside of academic spaces, previously one of my only “comfort zones.”

I also got to go outside once or twice. In March, I went back to Death Valley for a yet another outreach trip at a dark sky festival, although strong winds ruined most plans of stargazing and prevented us from camping outside (instead doing some sort of sleepover on the floor of the Furnace Creek Visitor Center).

At the end of the school year, Linhao proposed one last stargazing trip to the vicinity of Joshua Tree before heading out to his new shiny postdoc in Princeton. A day or two before we went, there was widespread news of a powerful solar storm. By sheer coincidence, our stargazing trip took place during a short period of intense auroral activity at low latitudes.

Also by sheer coincidence, the four of the rest of us who weren’t Linhao would end up in the same office for my last year of grad school (this following Linhao’s vacating of the same office not long before). This made for the greatest office name sign I could possibly imagine.

Our family came very close to having a catastrophic tragedy, one which reminded us to treasure life and make the most of it. In January, less than a week before his sixtieth birthday, my dad was the victim of a car accident in which an out-of-control sports car spun through a near-empty intersection, ramming into my dad’s car and causing it to flip multiple times. Despite the severity of the accident, my dad survived and, miraculously, suffered no permanent injuries.

This probably has something to do with why I bought a Lexus.

Year Five (2024–25): The Gauntlet

The final boss: getting a job

In my last year, I tended to get asked a lot whether I had written my thesis, or whether or not I was prepared for my defense. In reality, I wasn’t worried about these things at all. For me and many folks like me, the “final boss” was something else entirely.

In the academic path, the next step after getting a PhD is almost always a postdoc position. Most of these positions are “personal” (or “grant-based”) postdocs. These positions are opened by faculty who are looking for someone to do a specific project, usually the subject of a particular grant which is paying the postdoc’s salary. These are what most people in academia would think of when they hear “postdoc.”

More prestigious are “prize” postdocs, which typically have more formal competitions and fund postdocs to work on essentially whatever they want. The latter afford the postdoc a lot more independence and typically more autonomy over their funding. Compared to in other fields, prize postdoc positions are relatively numerous in astrophysics. Both of the previous PhDs from my group secured multiple prize postdoc positions at prestigious places with great science going on, so this became a model for what I was supposed to be doing next. During my job season, I only applied to positions like this.

Postdoc applications were, without a doubt, the worst academic experience of my entire life. This is in spite of the fact that I was ultimately successful. I think this sentiment is probably pretty common. Upon reflection, there are a few reasons for why this process is so incredibly unpleasant (focusing on prize postdocs in particular):

- Unlike in previous applications (undergrad, grad), in postdoc applications, the focus is on future projects—identifying research directions which could be interesting and selling them. Writing proposals is something that grad students (and theory students in particular) often don’t have much experience doing.

- Project timelines rarely see research projects wrap up right at the beginning of application season. However, incomplete projects (defined in our field by having an arXiv identifier) are much less compelling to hiring committees. As a result, the applicant is very often frantically trying to push one or more papers to completion at the same time as they are writing applications.

- In certain disciplines (like mine), it is common to go on a “job talk tour” to a subset of places you’re applying, in order to meet people at your target institutions and put yourself on their radar. You’re also on the hook for coordinating with all of the institutions to schedule your talks, hopefully adjacently to avoid redundant travel (e.g., combining East Coast trips together). So it’s often the case that you’re writing applications, finishing one or more papers, and giving talks simultaneously.

- Post-PhD careers include becoming a research faculty, teaching faculty, industry, or any number of other jobs. Postdoc applications are a natural catalyst to think about which of these paths are right for you, although colored heavily by imposter syndrome induced by gradually developing awareness of how few positions there are and how good everyone is.

- The application season keeps going and going. Every time I thought I was close to the finish line, there was some new stage of the boss to defeat.

Before the season started, I created a Discord server with some of my friends who I knew were also going through the application season. This ended up being incredibly valuable for my mental health, since it connected me with people who were going through really similar (but new) stressful experiences.

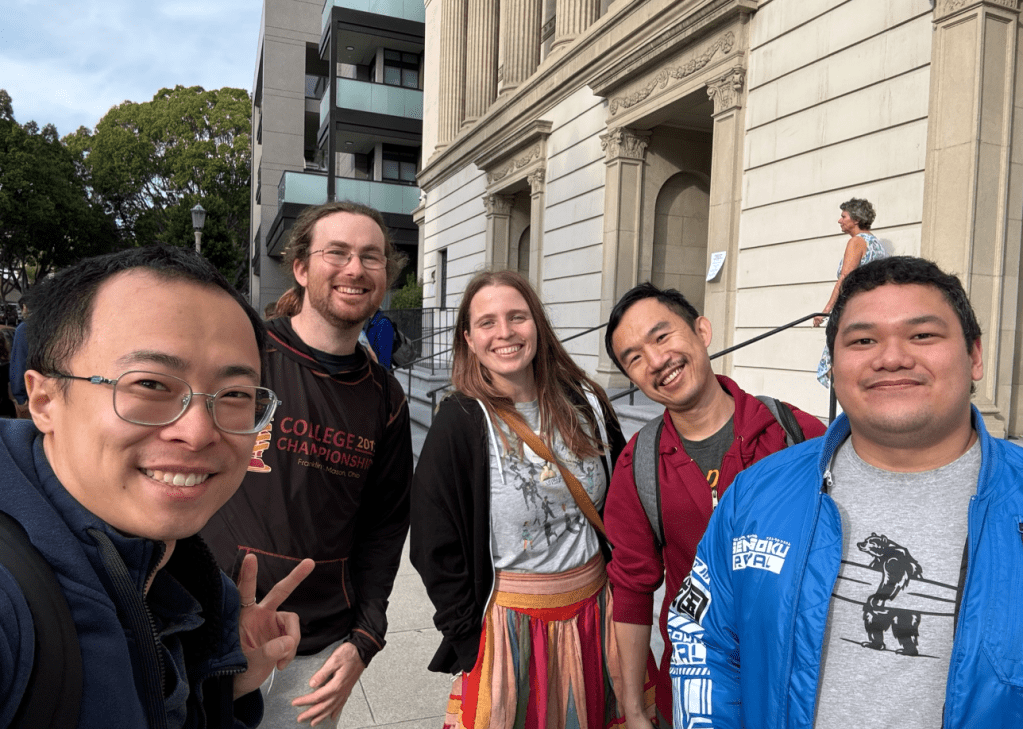

Besides some very early-deadline high-prestige institutional prize postdocs, my season really ramped up with the application for the NSF AAPF, a fellowship funded by the National Science Foundation which allocates three years of funding to fellows to take to a US institution of their choice. The application is deliberately structured to look like an NSF funding proposal (even down to using the same system) and requires around a dozen small random supplementary documents on things like how the data produced by the research will be made public and so on. A substantial fraction of the application is also judged based off of a concrete proposal for a Broader Impacts (i.e., outreach) activity, whose text is not really reusable in later applications. Naturally, I also submitted this application only a few weeks after a week-long trip to the Bay Area to visit UC Berkeley and UC Santa Cruz.

A highly successful application from the previous season told me that their application for the NSF AAPF wasn’t great, and that they needed to get “a bad one out of their system.” My experience was very similar to this: my NSF AAPF application wasn’t great, but it gave me a taste for what to expect.

The next major milestone was the NASA Hubble Fellowship, a prestigious fellowship which is awarded to 24 early-career postdocs based on a ten-page statement, a majority of which is a proposal for a concrete idea. I was applying for this postdoc at my childhood home in San Diego, my home base of operations for the early application season. Curiously, I remember spending an especially high effort on this statement in particular. I think this was because important mentors of mine had had the fellowship, and I probably wanted to emulate them. The 2024 Hubble Fellowship application was due on Halloween—it was hard to imagine something scarier.

Late in the previous school year, I had decided to work on asteroseismic constraints on white dwarf magnetic fields. Naturally, I decided I would finish the paper and put it on the arXiv before the Hubble Fellowship deadline. A week before the fellowship was due, I traveled to CIERA at Northwestern to give a talk—over the space of a few days, I would meet with people for hours by day and finish my paper by night. I was also writing and rewriting my Hubble application at the same time. I was also working with an earlier deadline: I needed to submit the Hubble application a day early before heading off to a two-and-a-half-week-long East Coast job tour. This, together with my East Coast job tour, was probably the most stressful part of the application season.

On the East Coast, I visited six institutions in four cities (New York City, Princeton, Toronto, Boston), giving talks at each and meeting with people for a few hours each day. Gone were the days of spending a few days carefully planning talk slides: I had to get really good at giving talks with five or ten minutes of specific preparation, copying and pasting slides together and banking on the fact that I knew my own science. I got really good at giving the same talk over and over again. Somehow, I think this workflow is about to become the norm for me.

Travel really started to lose its novelty around this point, particularly in the process of hopping from city to city once every few days, dealing with all the logistics involved and adjusting to new environments. Around this time was when the bulk of institutional prize postdoc applications were due, so I spent a lot of time in hotel rooms and libraries writing and sending off applications. On the trip, I met a lot of really great people, had some really interesting conversations, and saw a lot of cool places. Nevertheless, I probably would recommend new applicants to visit many fewer places than I did. In hindsight, it was certainly not good for my stress levels to visit places I ended up not applying to.

Entertainingly, on one of the last days of my East Coast visit, I was Zoomed into a party at Kip Thorne’s house where Nadine Soliman and I were declared by the faculty to be the successors of the Öcsi Bácsi Award, an esoteric decades-old TAPIR tradition which had been put on hold during the pandemic. I will not even attempt an explanation here for what this award is for (although, to set the tone, I was christened Nicholas “the Harmonious”). It was a nice conclusion to weeks of stress, although I was disappointed to not be able to make it in person.

After returning from the East Coast trip, there was nothing I wanted to do more than get back to research. I already liked doing research before, but I didn’t realize how much I would miss investigating a scientific question without the urgency and pressure of securing my future. On the last day of my East Coast trip (when I was at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian), I decided to work on a long-festering idea involving phase-based signatures in obliquely pulsating stars. It was a huge breath of fresh air.

In mid-December, I received a call during a meeting with Jim that I let go to voicemail. Returning the call afterwards, I was given my first job offer: the CIERA Fellowship at Northwestern, the same place where I had first been exposed to theoretical astrophysics six years prior. To have something locked down—especially one of my top choices—felt like a net being set under me while standing on a tightrope a hundred feet up. I still had to walk the tightrope, but at least I knew the floor, and knew it was comfy. Working on science I liked while knowing I had a place to go was an island of bliss.

The peace was not meant to last. In the ensuing months, I had the “good” problem of multiple interviews, which were basically just more talks given small numbers of faculty. I’m glad that nobody told me about these: I think anticipating them would have made me much more stressed out. Between job talks and my various interviews distributed across the winter and spring, I gave sixteen talks in total. My last (and favorite) interview was the KITP Fellowship, which simply prompted: “We’ve read your research proposal, but what are you working on right now that has you most excited?” After a job season of talking about what I was going to do, there wasn’t anything I wanted to talk about more than the new science I was actually working on.

In late January, I got an email that I was waitlisted for the Hubble Fellowship, with an assessment that “fairly good chance that you will receive an offer.” According to a mentor of mine who sits on some NHFP selection committee, the process involves around a third of the (more than six hundred) most promising applications being distributed to subcommittees in groups of roughly thirty. Each subcommittee sends their top few choices to some master committee which, starting from scratch, ranks them in order. The top 24 then receive an offer, with the rest being put on a waitlist with varying assessments of the likelihood that they will receive an offer. In a typical year, perhaps a fourth of the initial winners decline the offer.

Again, I’m glad I didn’t know the gory details in advance.

Every year, at the culmination of the application season, there is a period of about one or two weeks during which there is a “tangled ladder” of folks in limbo, most of whom sitting on waitlists waiting for someone else to make a decision before they can make their own. Because postdoc applications can involve a lot of negotiation (“combination” of multiple offers is fairly common at the top levels), this can take a while. What results is a rapid cascade of decisions as an increasingly large cohort of applicants know with finality what offers are on the table for them.

As I was warned, people above me on the NHFP shortlist took their time making their decisions (and justifiably so). I spent about a week and a half planning for possible contingencies, until I learned (about five days before the decision deadline) that I had won the Hubble. I took another four days to work out my final arrangements, including my host institution. My choice, in turn, freed up some other waitlists which certainly made a few other folks happy somewhere out there.

It was over.

I took a long nap. My PhD defense would be cake compared to this.

A world back on the brink

As my PhD started in chaos, so it was destined to finish in it.

The 2024 presidential election occurred on November 5th, 2024, while I was visiting Princeton. I went to sleep pretty sure what the outcome would be; when I woke up, it was all over. People at the Institute for Advanced Study the next day were all despondent. I had a sober but comforting talk with a faculty there around the same pond where, in the movie Oppenheimer, Einstein and Oppenheimer discuss the consequences of nuclear weapons.

Trump would turn out (to the surprise of nobody in the know) to be terrible for American science. Once inaugurated, he and the “Department of Government Efficiency” (led by an increasingly unhinged Elon Musk) unilaterally instituted huge cuts across the public. The status of international students was (and still is) highly uncertain. In science, they had the NIH, NSF, DOE, and NASA in their crosshairs (and probably others). The fellowship which had funded me through my grad school years was to be dramatically scaled back, and holders of fellowships like the NSF AAPF (which kicked off my application season) would temporarily and sporadically have their salaries cancelled. As the holder of yet another governmental fellowship, my future was also uncertain. NHFP Fellow-run application-writing assistance and public archives of successful applications (which dramatically helped me write my own application) were taken down in a preliminary attempt to placate the administration. (if it helps; my own application can be found here) (edit 28 Aug. 2025: they have since been reuploaded here)

Grad school was destined to be a small peaceful island in the chaos of growing fascism in the country.

In the beginning of the year, the Los Angeles area was also affected by the Eaton and Palisades fires, the former of which affected me and the latter of which affected my sister, then an undergrad at UCLA. For a few weeks, the air everywhere in the whole city of Pasadena was perpetually smoky, and there was a high degree of uncertainty about everything from the cleanliness of water to whether would have houses at all at the end of all this. While Caltech (being across the 210 Highway from the Eaton fire) was spared, many students, postdocs, staff, faculty, and community members lost their homes.

Crossing the finish line

A lot of people told me that going through postdoc applications mentally prepares you to be a postdoc. I think that’s true. By the end of my PhD, I felt like I understood the “bigger picture” of astrophysics well enough to pose and solve problems largely on my own.

Once my postdoc decision was sorted, the task remained to wrap up loose ends, “write” my thesis, and defend my PhD. Here, “write” is in quotes because, typical of many students in my department, my thesis was a “staple thesis.” In other words, my PhD had enough complete papers in it that my thesis was a LaTeX document with my papers copied in practically verbatim (as if stapled together), with the only new content being a short introduction and conclusion. Despite this, I received a thesis prize, which was some nice validation for my to-date magnum opus.

For my last months, Jim was on sabbatical to the University of Tokyo and later the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. However, by this time, I was perfectly satisfied with casual weekly Zoom meetings, and didn’t feel like I needed much guidance anymore. I finished up my paper on phase signatures in oblique pulsators and got involved in a collaboration on white dwarf magnetism with some folks in Israel (where things are also not going great at present…). Despite the pressure being off, I spent most of my Saturdays and Sundays at the office, doing nothing in particular, just to feel something I guess.

My PhD defense (mandated fully closed-door by the department) was largely unremarkable, and, to nobody’s surprise at this point, I passed without incident.

I spent at least an equal amount of time preparing a publicly oriented talk for friends and family (informed heavily by my Astronomy on Tap talk the August before). Since this public talk had no formal connections to my real defense, I was free to cleanse the talk of jargon and pack it full of as many inside jokes as I wanted. Out of all of my end-of-PhD activities (including my graduation), this was probably the highlight, and the one that gave me the most closure.

Another thing a lot of people told me is that you should take a good, long, break at the end. I think that’s also true. Even though I knew how strenuous the whole process was, even I was surprised by how tired I was. I definitely felt a lot of brain fog that I didn’t expect, and it was difficult to make progress at my previous pace, especially in light of all of the graduation-related tasks that I had to do.

At present, I now feel like I have more good ideas than time to work on them. Things like giving talks and refereeing papers, both of which used to feel hard and unfamiliar, have largely lost their difficulty or novelty. I also noticed that I have suddenly started to get invited to stuff, whereas I was rarely invited before. The transition to postdoc is certainly going to require more conscious prioritization of my tasks as well as a thoroughly thought-through reallocation of my time.

In my remaining months (including one nominally as a Caltech postdoc), I had my fair bit of travel. I traveled back to Panamint Valley a final time for the Great Orion Dark Sky Festival, stopped by Irvine, CA to visit some friends, and went on a roadtrip up to Vancouver, BC in order to accompany a friend to her new, shiny postdoc there.

Work-wise, I also made trips to New York City and Vienna, Austria for some incredibly valuable academic events. Much more travel coming in the next few years.

Not too long after, my sister graduated herself with her bachelor’s in psychology and statistics (with a minor in theater) from UCLA, finding herself in a similar position as I was in five years ago. Despite grad school being longer than undergrad, it felt much shorter. It was yet another cue to reflect on how far I had come.

Goodbye, Pasadena.

Overall advice

Should I do a PhD?

As I explained in my blacksmith analogy at the start of this blog post, grad school is a relatively unstructured but specialized training into academic research. In grad school, you produce, albeit as a junior worker (which is why, contrary to popular belief, you almost never pay any tuition yourself and almost always are paid for your work, in STEM disciplines). I would go as far as to say that grad school is not school. Jobs in academic research are, however, rare.

In my own opinion, these facts have a number of important implications, relevant for those considering grad school:

- Because academic positions are so few in number, most PhD graduates do not stay in academia long-term. Although PhD programs certainly have a lot of struggle, make sure that, on balance, you enjoy your work and are feeling fulfilled. If you think you would regret doing a PhD if it turned out in the end that you had to leave academia, you probably shouldn’t be doing a PhD. The adventure itself should be enjoyed.

- Grad school is not the right place to “postpone” life and to cling to the structure of school where clear goals are set by a teacher or someone else in a position of authority. Because the “school-like” parts of grad school fade out over the PhD program, grad school should eventually feel like work anyway (and heavily intensive work at that). So, although it can often feel like grad school is the “default” next step, it isn’t: going to grad school should be a conscious and deliberate choice.

- Unlike high school or college degrees, the vast majority of people are not expected to get a PhD. It is not a general credential for getting any job. You should not go to grad school solely on the basis that a PhD will “increase your appeal to employers,” unless you have a concrete idea of what job you want and know that a PhD is needed. Although a PhD (especially in physics) may be viewed as a sort of “IQ test” by employers, this is probably marginal, and my impression is that it is almost certainly a bad return on investment.

- Many high-achieving students like knowing things—knowing the answer makes you feel smart. For the most part, grad school doesn’t make you feel smart, it makes you feel dumb. Being on the frontier of knowledge guarantees that you are in a near-constant state of uncertainty, and you need to wholeheartedly try new things to move forward with full knowledge that most of the things you try will fail. The high degree of specialization also means that everyone you talk to will know a lot of domain-specific knowledge you don’t, and your ego needs to be robust to the fact that other people will always know stuff that you don’t.

On the positive side, I enjoyed my PhD a lot, for reasons enumerated in the second person below. If you think that these reasons appeal to you, a PhD may be for you:

- You enjoy doing academic research, or at least think there is a reasonable possibility that you would. More specifically, you like the idea of advancing human knowledge and learning things that no human on Earth knows yet. This is a time-consuming and difficult process: it is a mode of learning with no grades or answer key.

- You enjoy having independence over your work and schedule. While autonomy develops over time in grad school and schedule flexibility is field-dependent, grad school is often about making judgment calls about what needs to be done next. Although there are underlying market-like forces in academia, for the most part you can explore topics based on curiosity rather than in service of what a higher-up thinks is profitable.

- You enjoy being in a high enthusiasm environment. Frankly, academic positions don’t pay as much as the level of education would suggest. That means that everyone who is in academia is interested in science. They like talking about science, hearing about new science, and coming up with new ideas or collaborations. In the spaces I’ve been in, most people are pretty genuine and don’t pretend to be interested in things that they aren’t.

A last word of caution: technical STEM subjects have a reputation for people who like doing solitary activities like reading, coding, etc. However, academia is all about communication—conveying your ideas and results through talks, papers, and proposals. Do not do academic research if you don’t want to talk to other people.

What is theoretical astrophysics?

My discipline of theoretical astrophysics is very broad (as reflected in the name). The field includes any attempt to model things which are in space. As you may have noticed, this includes pretty much everything.

The reason why theoretical astrophysics can exist as a discipline is because astrophysics is a field in which the problems are relatively easy to understand (although the answers are, of course, hard). Although astrophysical systems tend to involve complicated hydrodynamical and gravitational physics, much of this physics can be modeled using simple toy models which capture the essence of the underlying phenomena. The large amount of possible physics involved means that astrophysics has a highly interdisciplinary nature, with the correct description of a system arising from some subset of fluid dynamics, gravitational physics, electromagnetism, nuclear physics, materials science, geophysics, etc. Often the toy models have a wide domain of applicability across many systems. In my sub-discipline of stellar physics, for example, much of the math used to describe stars can also be used to describe planets, moons, white dwarfs, neutron stars, and other interesting systems. It is a grand exercise in asserting to nature that its personality is not as complex as it claims to be.

Somewhat uniquely, astrophysics is also a discipline with a high degree of empirical feedback. Rather than studying physics in a lab, most astrophysicists study systems which already exist in nature, using them as “experiments” to try and understand the underlying physics involved. Most of the pragmatics of the field involve trying to extract as much information about a system as possible without needing to get close to it. Observers are center stage and, as a result, theorists are often presented with new systems they cannot explain or get their hypotheses tested pretty quickly (often within years). I benefitted immensely from doing my PhD at Caltech, an observer-heavy school in which I was exposed to a lot of observational developments.

My specialty of asteroseismology also has the unique property that the assumptions underlying its theoretical underpinnings are pretty well-justified, and the observations are at the precision level. Asteroseismologists are usually most interested in the frequencies of stellar oscillation modes—these frequencies can be measured with very high precision (nowadays up to a few hundredths of a microHertz, for big space-based missions). Due to the wave nature of the phenomena, most calculations occur at linear order and look very quantum-mechanics-like. However, as most astrophysicists don’t have that much experience doing quantum mechanics or formal mathematics, knowing either allows you to make new theoretical discoveries which have been overlooked. It is also an exceptionally friendly and cooperative community.

Grad school as a theorist (in any field) has its own unique features. Unlike experimentalists in other disciplines, theorists’ working hours are usually flexible—you can, of course, think anywhere, and computer simulations, once launched, hopefully run without constant intervention. Math doesn’t break unless we were wrong in the first place: we don’t need to worry about our lasers breaking or our cells dying, and our PhDs being lengthened in consequence. Unlike observers, we also don’t need to stay up until the early hours of the morning observing (and only do so for reasons of recreation/masochism). In theory, the burden of truth is also not that things “are true” but that things are “probably (or at least plausibly) true.” This takes some pressure off, but also puts some abstraction between the theorist and the “real” physics.

People usually think of theorists as being “smart,” but, for the reasons above, I don’t think we really deserve it.

Theory has several unique challenges, though. Besides specialized domain knowledge and possibly close familiarity with a code or two, theorists mostly trade off of ideas. Since they don’t actively maintain an experiment or follow routine observing proposal cycles as often, they need to constantly generate ideas to survive. This can make periods of stagnation feel pretty bleak. Moreover, because theory projects are about exploring simple ideas, the feeling I have had at the end of most of my long-term projects is that the answer should have been obvious, and I should have only taken a week if I weren’t stupid. For me, some reassurance comes from explaining the project to other people who, in asking the same dumb questions you asked earlier in the project, affirm that those questions were not dumb after all.

How do I make the most of grad school?

True throughout but here in particular: these opinions are my own, and your mileage may vary.

While I have a lot of thoughts, I think most of my advice ultimately flows back to:

“Intend to grow, be clear, and be happy.”

By “intend,” I specifically mean the act of telling to yourself (possibly out loud) the reason why you are doing something, and shaping the way you do things based on the outcome that you want. You should only do things because you understand why it would be a good thing to do, not just because you’re “supposed to be doing it.” If you find yourself in the latter position, be sure to make a conscious assessment of whether it is really necessary.

By advocating “growing,” “being clear,” and “being happy,” I don’t mean to assert that you shouldn’t intend anything else. But I do think these can be easily forgotten pillars for success. What follows are a few examples from each category for what I mean.

Examples of “growing”:

- You’re unsure whether to apply to give a talk at a conference, because you’ve never given one before and probably won’t get one anyway. You’re intending to one day become an independent researcher, which means one day you have to apply for and give talks. All other things being equal, I recommend applying to give the talk—you may be underestimating your ability to get it accepted. More importantly, discomfort is an important part of a PhD because growing is uncomfortable. Academia is hard precisely because it demands that you to do uncomfortable things and, once you do them, it expects them. You may feel anxious writing a paper for the first time: once you’ve written one once, it’s expected of you. Then, you may feel anxious giving a talk for the first time: once you’ve given one once, it’s expected you. You may feel anxious working on your own idea for the first time: once you’ve done it once, it’s expected of you. And so on ad infinitum. No wonder people find this academia business stressful.

- You have an idea for a project and think it might be promising. You’re intending to one day become a researcher who can come up with and work on their own ideas. It is wise to talk it over with someone with more experience (e.g., your advisor). Even if your idea is bad (which, at the early stages, it probably is), you will learn a lot from understanding in detail why it doesn’t work. Jim has been the recipient of dozens of my project ideas (the vast majority of which bad), and I learned immensely from it. Moreover, towards the end of grad school, my project ideas were plausible enough that Jim stopped being able to tell that they were bad, and that resulted in two papers and a lot of new experience.

- You’re unsure whether to attend a talk that is outside of your field, and think your time would be better spent doing your own research. You’re intending to one day have a broader perspective on your field. In a vacuum, you should probably go to the talk (although there is some push-and-pull here). Consistent with advice I was told at the time, a lot of “off-topic” talks I watched later became very useful several years after the fact, like “sleeper agents” hiding inside my brain. Even when (in the usual case) I never end up needing that information, having heard it before made it a lot easier for me to have conversations with other researchers outside of my field. Also, quite frankly, as an early grad student, your time is not that valuable—I certainly view knowledge I gained from watching talks much more valuable than marginal day-to-day increases in progress, which smoothed out a lot over the five years I was in grad school.

- You’re unsure whether to sign up to talk with a visitor, since you don’t know what you would even talk about and think you would waste their time. You’re intending to get acquainted with the research in your field. An ultimately crucial part of this is to be acquainted with the researchers, too. I have found that someone explaining their work to me teaches me more than spending ten times longer reading their paper, especially if it is out of my field. Talking to people about research is also good practice. You’re also not wasting their time since it’s ostensibly the whole reason they’re there in the first place. In the worst case where you really don’t know what to say, just talk about the weather—it helps a lot long term to have met a lot of people, which requires meeting them in the first place.

The theme here is to try new things early and often, since those skills “gain interest” over time.

Examples for “being clear”:

- You want a faculty member to fill out an online form. You’re intending to get a person with very tight time constraints and a full inbox to do something simple. It follows that you should make it as easy as possible to figure out (1) that they need to do something and (2) what it is. Therefore, the email should be short, with the important action bolded/underlined or otherwise emphasized, and with some very conspicuous tag like “[action needed]” included in the title. This may feel overly direct and “impolite,” but will be much more appreciated than a lengthy email which avoids being too “forward” about what is being asked for.

- You want to get approval to submit a paper with multiple collaborators on it. You’re intending to move forward a project while giving collaborators a chance to say their piece. It follows that you should make it as easy as possible for progress to happen. Structure your interaction so that progress results from being passive (the easy thing) rather than being active (the hard thing). Instead of asking your coauthors to all give the go-ahead to submit a paper (which could take forever), tell them a deadline by which you will submit the paper, and invite them to give feedback or ask for an extension (which they will only do if they have some active concern).

- You are unsure about how to discuss paper authorship order with collaborators. You’re intending to navigate an awkward conversation while learning how to handle similar situations in the future. It follows that you should ask your advisor for advice (assuming there is no clearly articulable reason why not). After all, as your advisor, they have some explicit investment in your professional development. Asking about the pragmatics of being a scientist can be awkward (“Am I even allowed to ask that?”), but ultimately beneficial in the long run.

Examples for “being happy”:

- You don’t like your project. You’re intending to work on something you’re interested in that you think is promising. You should start a dialogue with your advisor about the future direction of your project and, if it doesn’t seem promising, whether there are any natural off ramps and/or alternative projects. The answer to this might be no, but a responsible advisor should reciprocate the discussion (relevant caveats apply). Also, ultimately, you know the day-to-day details of your project better than your advisor, and you will usually know better what works (versus what “should work”).